Monfort Professor Award

Candidate’s Action Plan

Monfort Family Foundation 2003-2004

Human activities (primarily combustion and forest clearing) release about 7 billions tons of carbon into the atmosphere every year as CO2, raising serious concerns about possible future climate change. Less widely known is the fact that only about half of this CO2 remains in the atmosphere because of poorly understood “sink” processes on land and in the oceans which sequester the remainder. My research program seeks to develop a quantitative accounting of these sinks, through a process known as “inverse modeling.” Basically, we use measurements of subtle variations in CO2 concentration in space and time and then, accounting for the trajectories of air upstream of each sample, estimate the rates of emission and uptake of the gas at the Earth’s surface by mass balance.

Up to now, inverse modeling of the carbon cycle has used time-averaged data from a network of about 75 sites in remote areas of the world at which flasks of air are collected weekly. For the past several years, I have argued for a greatly expanded set of observations of CO2 in the atmosphere to facilitate much more precise location of CO2 sinks through enhanced inverse modeling techniques. The US government is planning a major push in this direction in the middle of this decade, known as the North American Carbon Program (see http://www.CarbonCycleScience.gov). The carbon science community is about to move into a brave new “data rich” world in which CO2 variations in the atmosphere are very well characterized (at least over the USA), and an abundance of other new information is also coming online. This will include in-situ data as well as a flood of new satellite imagery. The modeling approaches we have used in the past (both “forward” simulation models and inverse models) will be inadequate in the new “data rich” world. We modelers are going to have to create a new set of tools to extract the information about sources and sinks from the new data sources. If we are successful, this science is going to undergo a revolution in the next ten years, leading to a much deeper understanding not only of where the CO2 is going, but of the functioning of the global biosphere itself.

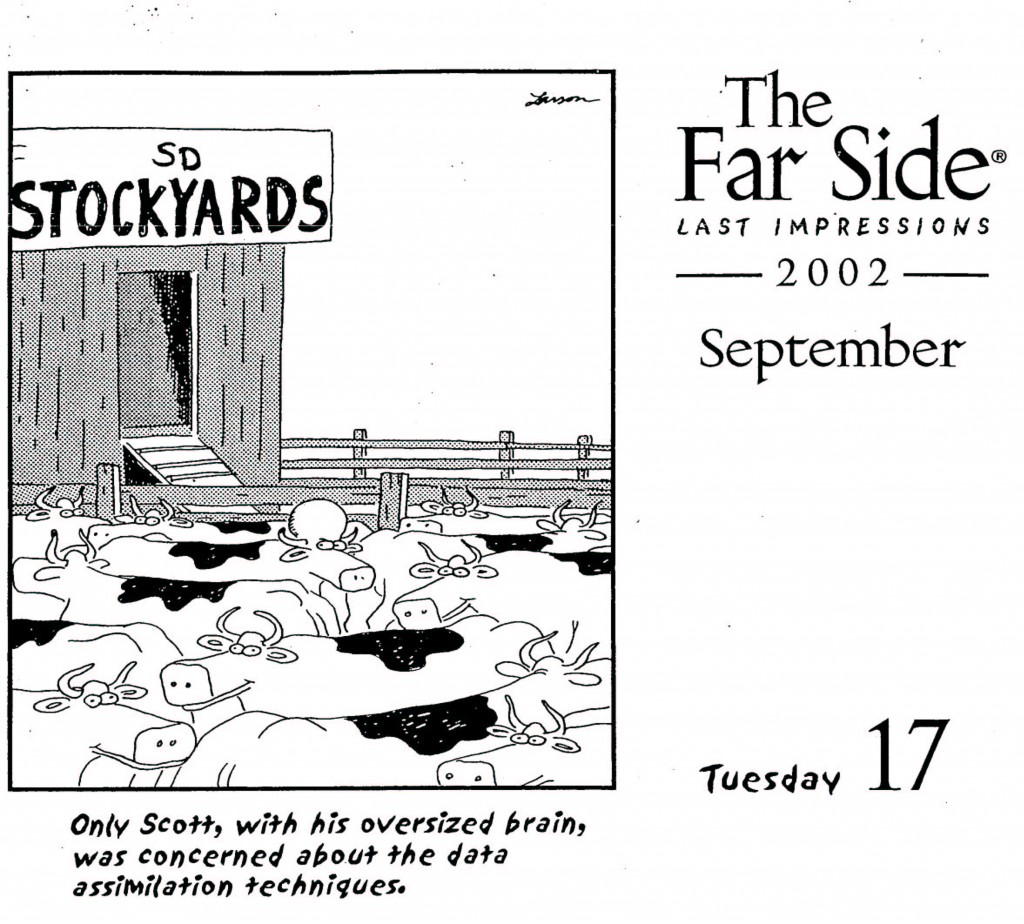

A particularly promising set of techniques for analyzing large volumes of disparate data on coupled geophysical and biogeochemical phenomena is known as “data assimilation” or “model-data fusion.” These techniques, developed and applied widely in weather forecasting and seismic exploration, involve forming statistically optimal combinations of data and the output of process-oriented simulation models of the phenomena in question. The result is a set of estimates of the desired quantity (in our case, time-varying global maps of CO2 uptake by various processes) which are optimally consistent with both the observations and with the known physical and biogeochemical laws that govern the relationships among the variables. The idea is to find the description of the processes controlling the CO2 sinks that can simultaneously match the observations of the air, land, and water made by towers, satellites, aircraft, ships, and laborious field sampling. We believe that CSU is poised to become a world leader in data assimilation and model-data fusion. Support from the Monfort award will allow a significant step to be taken to position Colorado State University for leadership in these areas.

The mathematical techniques used in data assimilation are well developed but relatively obscure and difficult to learn, requiring a background in statistics and the calculus of variations. Unfortunately, there is a serious shortage of people in these fields who know anything about the carbon cycle, and vice versa! I have been quite successful in obtaining support for my research program, but I must compete with a number of other scientists in Universities and research laboratories around the world for the very limited pool of skilled people to work on my projects. There are no organized degree programs in carbon data assimilation, nor are there good textbooks. We are inventing the field as we go. I recently helped to organize a two-week summer study institute on this subject at the National Center for Atmospheric Research (NCAR) in Boulder. This was a good start, but much too short and cursory to develop real expertise in the participants, though we did attract a number of really excellent students.

If I am awarded the Monfort Professorship, I plan to build and teach a full semester course in data assimilation for the study of the carbon cycle. I would recruit experts from among those that gave 1-hour lectures at the NCAR summer institute, and work with them to develop formal teaching materials. These would include formal lectures, numerical tools, and a progressive series of rigorous exercises which would allow graduate students or postdocs to develop understanding and skills one step at a time. The objective would be to train the next generation of scientists who will become the leaders in this exciting new revolutionary phase of carbon cycle science over the next decade and beyond. Major research efforts in the carbon cycle are also ongoing at the Natural Resource Ecology Laboratory and the Departments of Forest Science and Rangeland Ecosystem Science. Graduate students in those departments and in the Graduate Degree Program in Ecology would benefit from the course. Colorado State is a member of the Consortium for Agricultural Soil Mitigation of Greenhouse Gases (CASMGS), a major regional center for carbon cycle research. All these efforts would be substantially enhanced by the proposed course and the University’s emerging position as a source of expertise on carbon data assimilation.

In year one of the Monfort Professorship, I propose to recruit a Research Scientist to work with my group on carbon data assimilation research. This person would be supported 3 months by the Monfort funds, and 9 months by an existing NASA contract. In addition, I plan to invite scientific visits from noted experts in this field, and to work closely with them to develop lectures, exercises, and other course materials. I would use my existing research staff to develop the numerical tools and simulation models needed for a successful “hands-on” laboratory portion of the new course. I intend to develop this new course from the beginning for web-based instruction. All course materials, including lectures, exercises, and even simulation modeling activities, would be available remotely through the world-wide web. This will allow the material to reach the widest possible audience of talented young scientists around the world, and will extend the impact of the Monfort gift far beyond Colorado State University.

In year two, I would offer the course as a Group Study or Practicum jointly between the Atmospheric Science Department and the Graduate Degree Program in Ecology, where I also hold the rank of Advising Faculty Member. The experience gained in teaching the course live would be used to modify and improve the web-based curriculum developed in year one. The new Research Scientist would be supported half time by Monfort funds in year two, and would transition to 100% research contract and grant support after the Monfort Professorship ends.

A two-year budget is attached below. I would be primarily responsible for developing the scientific content of the course. Mr. Kleist and Ms. Uliasz would be responsible for programming, web development, and implementation of the online materials. All salaries are charged fringe benefits and rates are assumed to inflate at 4% from year 1 to year 2. The remaining funds would be used to defray costs of scientific travel and, honoraria for the visiting experts I plan to recruit to help with the course development, and for computing support for the new research scientist.